Dr. Carter G. Woodson began the holiday in 1926 amid the cultural renaissance among Black people in the United States

By Abayomi Azikiwe

Editor, Pan-African News Wire

Thursday February 5, 2026

Historical Review

On this 100th anniversary of the founding of “Negro History Week” in February 1926, the field of African American historical studies continues to be denigrated and marginalized by the administration of United States President Donald Trump and his supporters within the ruling class.

Dr. Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950) had earlier formed the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLAH) in 1915 and during the following year the Journal of Negro History appeared on the scene in 1916 providing a platform for research being conducted in the field by various scholars.

Woodson, due to the oppressive and racist conditions prevailing during the late 19th century in West Virginia where he was born as well as other Southern states, was forced to delay his primary and secondary schooling. Later he attended Berea College in Kentucky, the University of Chicago and later received a Phd from Harvard University in History. Woodson worked as a teacher and administrator in Washington, D.C. and later at Howard, a Historically Black College and University (HBCU).

He would later become dissatisfied with the African American education model in operation during the post-Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras. A debate surfaced during the late 19th and early 20th centuries largely personified through the ideological struggle between Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois, an earlier African American graduate from Harvard University, in opposition to Booker T. Washington, the founder of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

Washington struck a conciliatory tone as exemplified in his 1895 Atlanta Compromise speech claiming that African Americans should focus on self-help and “industrial” education as opposed to the “liberal arts”. Du Bois and others such as William Monroe Trotter, believed that Washington was selling out the African American masses by rejecting the need for basic civil rights, universal suffrage, quality modern education and freedom from persecution.

Between the 1880s and the post-World War II period, more than 4,000 African Americans were lynched in the U.S. After the Civil War a series of Constitutional Amendments and Civil Rights Acts were passed by Congress in the late 1860s and 1870s. Yet, by the early 1880s the reversal of the letter and spirit of these legislative measures were completely overturned.

By 1896, just one year after Washington’s Atlanta Compromise speech, the deceptive ruling in the Plessy v. Ferguson Case enshrined the false notion of “separate but equal” within the canons of Constitutional law. It would take a series of rulings leading to the Brown v. Topeka case of 1954 to formulate the concept that “separate but equal” was inherently discriminatory and unconstitutional.

Woodson viewed the contours of African American education as articulated and funded by the U.S. ruling class as lacking in what was actually needed to foster progress and development. Consequently, he left public and higher educational institutions to formulate his own organizations which funded and published his research interests related to African American historical studies.

After joining the West Virginia Collegiate Institute (WVCI) he worked closely with President John Davis to increase enrollment at the school. He went to WVCI after leaving Howard University due to disagreements with the administration.

In an entry posted on the West Virginia State University website, it notes of Woodson’s work:

“As director of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Woodson launched the annual celebration of Negro History Week in 1926. He chose the second week of February for the annual event to commemorate the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. Woodson sent out a veritable flood of literature promoting the event, emphasizing the importance of recognizing black achievements and contributions, and suggesting various ways to celebrate the week. As Woodson later wrote, the education departments of three states, North Carolina, Delaware, and West Virginia, celebrated the event in its first year, and he was frankly surprised by the favorable reception to his idea. Notable African American contemporaries, including W.E. B. DuBois and Rayford Logan were impressed. DuBois considered it one of the greatest accomplishments to come out of the 1920s. The weeklong celebration was expanded into Black History Month in 1976 by President Gerald Ford who used a Bicentennial address to urge Americans to ‘seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of black American s in every area of endeavor throughout our history.’” (https://wvstateu.edu/about/history-and-traditions/notable-alumni/carter-g-woodson/)

Chapters of the Association for the Study of Negro (later African American) Life and History (ASNLH) were formed in various cities and regions of the country. Woodson would tour the U.S. delivering lectures and promoting his publications.

Further Popularization of African American History

During the period of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s through the Great Depression and World War II, Woodson would continue his lecture tours, publications and the building of the Association. He was a prolific writer for African American newspapers such as the Baltimore Afro American, Pittsburgh Courier, New York Age, among others. (https://biblioskolex.wordpress.com/2023/08/29/carter-g-woodson-in-the-new-york-age-1931-1938/)

The writings of Woodson dealt with the absence of African and African American history from the curriculums of primary, secondary and higher education institutions. This was largely true even among those segregated colleges and universities designed for the higher education of African Americans. Many of the ideas advanced in Woodson’s newspaper columns were presented in his well-known work entitled “The Miseducation of the Negro”, published during the Great Depression in 1933. (https://1619education.org/sites/default/files/2023-02/Preface.Mis-Education%20Of%20The%20Negro.pdf)

Several years after the conclusion of WWII, the Cold War became full blown impacting the political will of the education system to correct the falsehoods and omissions related to African American history and contemporary affairs. The struggle for civil rights had dispersion cast upon it as being “communist influenced” by emphasizing its role in movements against racism and for an anti-imperialist foreign policy.

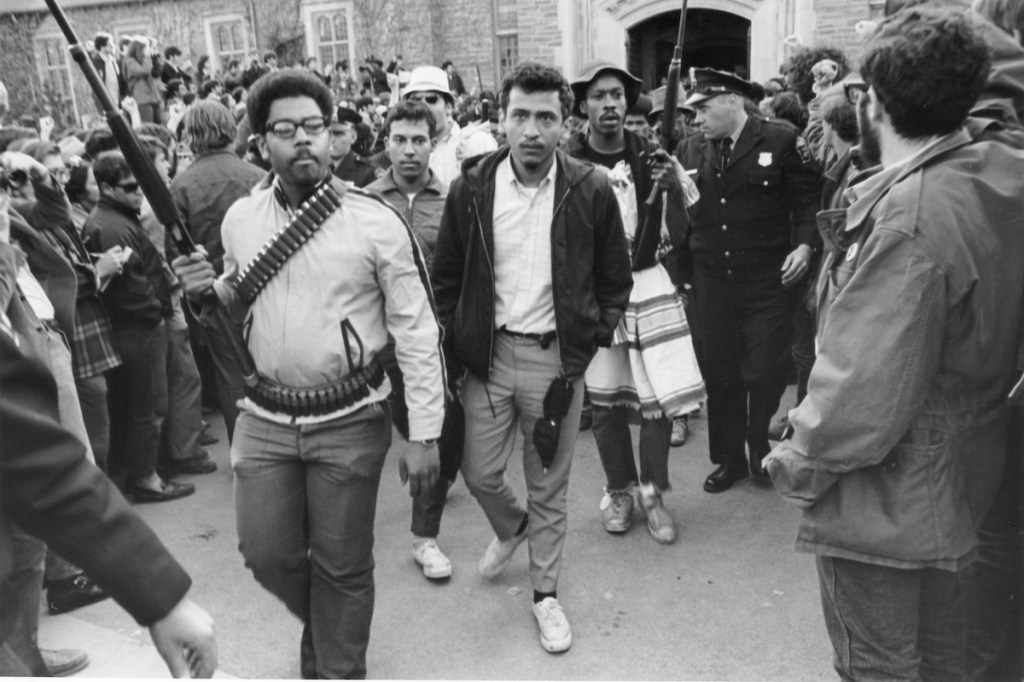

However, by the beginning of the 1960s, an entire decade since the death of Woodson, the emergence of the African American youth movement as exemplified by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), began to throw off the restraints imposed by the Cold War paranoia about a “communist threat.” By the mid-to-late 1960s many of these youth came out solidly against U.S. foreign policy particularly the war in Vietnam and opposition to support by the Pentagon and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) for colonial regimes still operating in Africa and other geo-political regions of the world.

Along with the demand for civil rights, political empowerment and the end of imperialist wars were the calls for curriculum reforms in all levels of education. The resistance to the demand for Black and Pan-African Studies during the late 1960s through the 1980s must be viewed within the broader social context of African American movements for substantive and revolutionary change. The direction of education has always been a reflection of the values and interests of the U.S. ruling class. Hence, the debate over the character of African American education during the late 19th and early 20th centuries holds tremendous political lessons for the current period.

The Perils of African American Historical Studies Under the Trump White House

One year after the beginning of the second non-consecutive term of the Trump administration, the attacks on broad segments of the U.S. population have been unrelenting. From the effective liquidation of the Department of Education to the withholding of research grants to higher educational institutions, has clearly illustrated the regime’s hostility towards scientific inquiry.

As part and parcel of this anti-intellectual onslaught is the further mental erasure of African people and other oppressed nations in the U.S. and around the world. The failure to recognize the actual historical trajectory of capitalism and imperialism in the U.S., even though the ruling class has benefitted from these exploitative systems, remains a cornerstone to the war propaganda of the far right.

A recent example was the removal of a monument acknowledging African enslavement in the first capital city of the U.S., which is Philadelphia in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. These actions are in line with the Trump administration’s attempt to obliterate the historical memory related to enslavement, colonial rule and economic exploitation.

A January 30 report published by the Associated Press explained that:

“A federal judge warned Justice Department lawyers on Friday that they were making ‘dangerous’ and ‘horrifying’ statements when they said the Trump Administration can decide what part of American history to display at National Park Service sites. The sharp exchange erupted during a hearing in Philadelphia over the abrupt removal of an exhibit on the history of slavery at the site of the former President’s House on Independence Mall. The city, which worked in tandem with the park service on the exhibit two decades ago, was stunned to find workers this month using crowbars to remove outdoor plaques, panels and other materials that told the stories of the nine people who had been enslaved there. Some of the history had only been unearthed in the past quarter-century.” (https://apnews.com/article/slavery-exhibit-removed-philadelphia-trump-executive-order-cd55e4f2a0d2a528540f73911972f677)

These state actions of repressing African American history must be resisted on various levels. African Americans and other interested parties could return to organizing their own history clubs, study groups and independent publishing houses in following the example of Woodson beginning even more than a century ago. Such independent activities will be conjoined with political campaigns to end institutional racism and foster full equality and self-determination.

—

———————————————————–

Distributed By: THE PAN-AFRICAN RESEARCH AND DOCUMENTATION PROJECT–

E MAIL: panafnewswire@gmail.com

==============================

Related Web Sites

http://panafricannews.blogspot.com

michiganemergencycommittee@blogspot.com

http://moratorium-mi.org

http://www.world-newspapers.com/africa.html

http://www.herald.co.zw/

You must be logged in to post a comment.